Report: A reality check on capital markets union

November 2020 • The future of EU capital markets • by Panagiotis Asimakopoulos and William Wright

This report analyses the development of EU capital markets since the conception of the capital markets union initiative and shows that while steady progress has been made at an overall EU level, growth has been patchy and there is still a lot of work to be done in individual member states.

New Financial is a social enterprise that relies on support from the industry to facilitate its work. If you would like to request a copy of the full report, please click here.

At a time when Europe needs bigger and better capital markets more than ever to help support a post-Covid economic recovery, the latest report from New Financial on the progress of capital markets union is a sobering reality check.

The report analyses the progress in capital markets in the EU27 since the launch of the CMU project in 2014, and measures growth at a granular level across 24 individual sectors of capital markets and in each of the 27 member states.

On the one hand, at an overall EU27 level capital markets are heading slowly but steadily in the right direction: broadly speaking, capital markets are growing both in size and depth relative to GDP. But on the other, when you zoom in on the progress at an individual country level, the picture is much less promising. In many cases the gap between those countries with well-developed and those with less-developed capital markets is widening rather than narrowing.

At its most basic level, capital markets union is about reducing the reliance of EU companies for their funding on bank lending and reducing the dependence of EU savers for their future financial security on bank deposits. These two measures highlight the dichotomy with CMU. Over the past five years, the EU27 economy in aggregate has become less reliant on bank lending as more companies have turned to the corporate bond market – but the reliance on bank lending has increased in 11 of the EU’s 27 members, and the vast majority of the shift to corporate bonds is accounted for by just a handful of countries.

In more positive news, pools of long-term capital in the form of pensions and insurance assets have grown across the EU, but the proportion of household wealth sitting in cash savings has stayed stubbornly high and remarkably constant over the past five years.

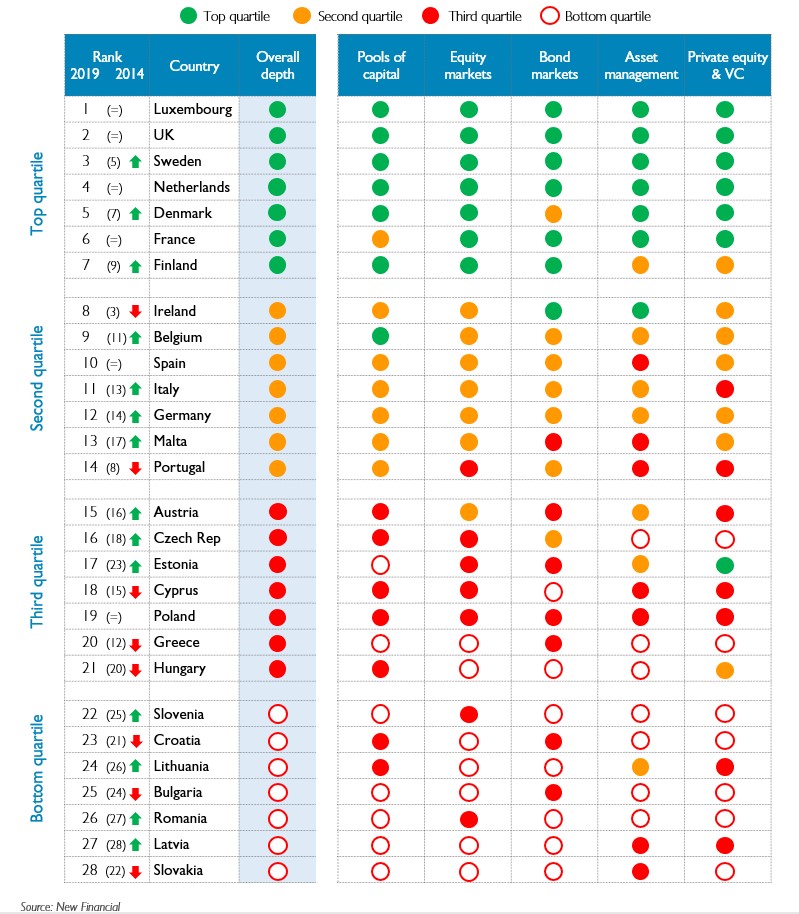

The depth of capital markets relative to GDP in individual countries (across 24 sectors of activity):

A long-term game

We have argued from day one that CMU is a long-term game and will take decades to become a reality. In this report we do not attribute any growth in EU capital markets over the past five years to CMU itself – it’s far too early for that – nor do we blame CMU for a lack of progress.

Instead, at a time when the EU economy needs all the help it can get, this report highlights the increased urgency of the CMU project in the wake of Brexit and the Covid crisis. We hope the report acts as a wake-up call to member states in underlining the need to step up a gear in building bigger capital markets from the bottom up, and helps support the argument for more radical action at an EU-wide level for top down reforms and for better outcome-based metrics to measure progress.

In the global financial crisis more than a decade ago, capital markets were a big part of the problem. In response to Covid, we think they are a big part of the solution. They have responded well so far in providing additional funding for the economy, and we think they can play a bigger role in future in helping to drive an economic recovery by boosting the competitiveness of EU companies and supporting jobs, investment, future financial security, and the transition to a more sustainable economy for the benefit of European citizens. However, the recent surge in emergency bank lending in response to Covid is likely to have reversed a lot of the progress made so far.

In September the European Commission published a new action plan for CMU for the next five years to a mixed reception. On the one hand, the plan has been criticised for lacking vision and ambition, for avoiding the detail, and for not addressing some of the big politically-sensitive areas such as supervision. On the other, it has been praised for being more practical, achievable and more focused than previous iterations. While the new action plan is unlikely to be a game changer on its own, this report argues that it should be embraced by member states as the best way to lay the foundations for bigger and better capital markets in the longer term.

Here is a 10-point summary of ‘A reality check on capital markets union’:

1. A strong backdrop: at an aggregate level EU capital markets are heading in the right direction. The value of capital markets activity has increased since 2014 in all but four of the 27 different sectors we analysed by an average of almost 40%, and the overall depth of capital markets relative to GDP has grown by 14% in the five years since the launch of CMU. While this growth is welcome and provides a strong backdrop for the CMU project, it is too early to be directly attributed to it.

2. A mixed picture: at an individual country and sector level, the picture is less promising. Capital markets have shrunk relative to GDP in a third of the 27 member states over the past five years and the availability of funding for corporates has fallen in real terms in more than half of them. In key sectors like equity markets and corporate bond markets, activity has shrunk relative to GDP at an EU level and has fallen in more than half of countries.

3. Mind the gap: while capital markets in the EU27 are bigger and deeper than they were before CMU, they are still relatively underdeveloped. On average, capital markets across the EU27 are half as large relative to GDP as in the UK, which in turn is roughly half as developed as the US. In more than half of the sectors we analysed, capital markets in the EU27 have grown at a slower pace over the past five years than in the UK and US.

4. A wide range in depth: there is a wide range in the depth of capital markets across the EU. The good news is that there are a number of countries in the EU27, such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and France with well-developed capital markets that can lead the way in terms of the future growth across the EU27. On the other hand, capital markets in large economies such as Germany, Italy and Spain are significantly under-developed and they may struggle to play a significant and much needed role in supporting the economy post-Covid.

5. A lack of convergence: the range in the depth of capital markets across the EU has widened rather than narrowed since 2014. The small number of countries which already had well-developed capital markets in 2014 have seen the highest growth in capital markets over the past five years, while countries with less-developed capital markets have in most cases struggled to gain momentum in closing the gap with the EU average.

6. The reliance on banks: companies in the EU are still heavily reliant on bank lending for their funding. While significant progress has been made at an overall EU27 level over the past five years – the average share of corporate bonds in total borrowing has grown from 19% to 23% – companies have become more reliant on bank lending in 40% of member states. Three quarters of the growth in corporate bond markets has come from just four countries, and in a third of countries the value of corporate bond markets has gone down.

7. Deeper pools of capital: deep pools of long-term capital are the foundation of deep capital markets so it is encouraging that the value of pensions and insurance assets has grown in every country in the EU27 since 2014 and increased relative to GDP in all but a handful. While the proportion of household financial wealth sitting in bank deposits is still high (at 32%) the reliance on cash savings has decreased in two thirds of member states and the value of investment in equities, bonds, and funds has grown in real terms in all but three.

8. A renewed sense of urgency: Brexit and the Covid crisis have injected a new sense of urgency into the CMU project and underlined the need for more capital markets to help fuel an economic recovery than ever before. The new action plan published last month by the European Commission reflects this urgency and the language used in the action plan is designed to win political support across member states at the highest level.

9. Striking a balance: any grand project like CMU involves a trade-off between ambition and achievability, and between impact and timeframe. The new action plan may lack vision and concrete proposals in politically sensitive areas like supervision and it will not be a game changer on its own. But it is more practical and focused than previous versions, and makes useful proposals in areas that can have a longer-term impact such as retail participation and company information that will help lay the foundations for the next phase of CMU.

10. Pulling the big levers: building deeper and more integrated capital markets will take decades and long-term success depends on a long-term commitment by members states and the implementation of both bottom up measures and top down EU-wide initiatives. The Commission and member states can and should work together to develop more radical and high impact proposals to accelerate CMU in the next few years.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Panagiotis Asimakopoulos at New Financial for conducting much of the heavy-lifting in this report; to Dealogic for providing much of the data behind it; to the many individuals who have fed into the analysis through our events over the past few months, and to our members for their support for our work in making the case for bigger and better capital markets in Europe.